|

"There is always inequity in life.

Some men are killed in a war and some men are

wounded, and some men never leave the

country...

Life is unfair."

John F. Kennedy in a press conference on March

21, 1962

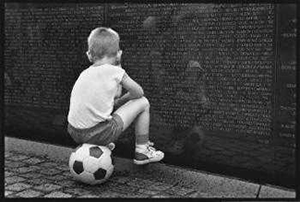

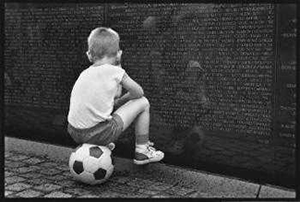

What follows is now history. At that time, long

ago and far away, it was very much the present,

and for many it can never be history, for they can

neither forget it nor confine it to their past.

Pictures that speak for themselves can perhaps

provide the most honest and straightforward view

of what war can be. The text below is excerpted

and paraphrased from a letter to President Nixon

sent during the summer of 1970 and published in

LOOK Magazine on July 28, 1970.

"They have been in a war for years and years

and they are quite debilitated and decimated,

and I don't think they are capable with any

kind of resistance of continuing this fight."

Spiro T. Agnew, Vice-President of the United

States

Face the Nation (CBS-TV)

May 3, 1970

I had been practicing neurosurgery before my

commissioning, and naturally enough assumed I'd

soon be in Vietnam. The army does move in strange

ways at times, and I found myself outside Tokyo

for somewhat less than two years. C-141 transport

planes would pick up our patients at various

staging facilities in South Vietnam, wherever

large enough airfields were secure, and would fly

them to the next hospital in the evacuation chain.

This meant the Philippines, Japan, occasionally

Okinawa or the United States. We were privileged

at the 249th General Hospital in Japan to see the

majority of seriously injured patients with wounds

of the central nervous system, and thus had a fair

overview of how things were in military

neurosurgery during this time.

I'm certain that many of our patients would not

have survived long after initial wounding in

previous wars. It was not unusual for us to

receive gravely brain-injured men who had had

their initial brain surgery within one to two

hours of wounding. Needless to say, because of the

tactical situation, it was sometimes impossible

for a helicopter to reach a man for twenty-four

hours or more, but these isolated delays were more

the exception than the rule.

The 249th General Hospital, where I worked, was

located in Asaka, just northwest of Tokyo. It was

a one-thousand-bed general hospital. We received

about one thousand wounded each month and either

evacuated or returned to duty slightly less than

that number. The hospital gates were manned by

local Japanese security guards, and the hospital

complex was protected by a high wire fence.

"I would never send troops there."

Dwight D. Eisenhower

General, United States Army

New York City

June 8, 1952

Each ward in the hospital had its own medical

flavor, and one could tell at a glance which

subspecialty was represented. We had a full

service hospital of course and did just about

anything you could think of, except for organ

transplants.

The two neurosurgical wards had between sixty and

eighty beds. and the evacuation system kept our

census fairly high. We had two fully trained

neurosurgeons, myself and a surgeon from southwest

of Worcester, Mass. All our patients had something

wrong with one part or another of their nervous

system--usually something was missing after

injury. Although we usually kept patients between

five days and several weeks, the turnover could be

quite brisk. During times of stress--for instance,

during Tet when the enemy was acquiring its

psychological victory--we continued our patients'

evacuations to the United States as briskly as

possible. I would usually write out the patient's

discharge and transfer summary at the same time

that I did his admission history and physical.

May I suggest that if another 'Tet-like' period

occurs in this non-war, it would save a lot of

time and effort if patients were sent directly

back to the United States from Southeast Asia

rather than to Japan. Undeniably, Japan is a

wonderful land, and its culture is fascinating,

but so few of our patients really enjoyed the time

they spent there. Mostly, they wanted to know why

they had come to Japan, and what were they doing

in that part of the world. I never really did find

the answer to that question in my one year, eleven

months and twenty-eight days of active duty, and

must further confess that I never heard a very

reasonable explanation of what any American was

doing over there.

"Vietnam has been good for the Marines, and

the Marines have been good for Vietnam."

Herman Nickerson, Jr.

Lieutenant General, U.S. Marine Corps

Danang, South Vietnam

March 9, 1970

I wonder if you ever got that report from the

costs analyst who visited with us in Japan. He

came from the Department of Defense. I tabulated a

list of patients on our ward about that time, and

tried to determine from a medical point of view

what percentage actually benefited in their

treatment by coming to Japan instead of taking an

extra five or six hours to go directly home. We

had somewhat more than sixty patients on the two

wards then, and I could honestly say that two or

perhaps three of them might have benefited by not

taking the more direct route. I'm not quite

certain of the final figure the Pentagon was

given, but I was told that the costs analyst

received from our medical command in Japan the

statement that fifty to fifty-five percent of our

men benefited from their time with us. It is

interesting to see how the assessment of the

situation varies depending from what level in the

chain of command you are watching.

Many of our patients with severe degrees of brain

injury showed very little resentment against the

circumstances that found them in Vietnam . In one

sense, the more severely brain-injured were

fortunate in that they were less aware of their

deficits and certainly experienced less anguish. I

doubt the same would hold true of their families.

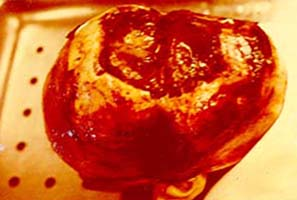

I was never entirely satisfied with treating one

particularly severe type of problem. Briefly, the

difficulty arises because such a large amount of

nose, middle face, and base of skull are

destroyed, along with brain substance. Infection

and continued leaking of spinal fluid were most

difficult to manage. I do not think we have found

an ideal way yet of treating this type of injury.

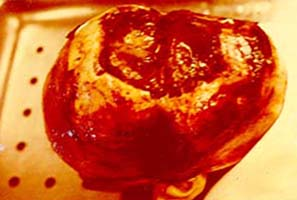

The loss of tissue in land-mine injuries was

rather common. Such wounds were extensively

debrided in Vietnam, and after five to seven days

of care, they were either further debrided of dead

and necrotic tissue or sutured. Many of our men

had multiple-fragment wounds from rockets, land

mines, booby traps or mortars. When the brain or

spinal cord was also damaged, they'd be assigned

to our neurosurgical service and we'd have an

opportunity to extend and broaden our general

surgical experience with caring for these

associated injuries.

"So I really personally believe the

introduction of U.S. ground troops in South

Vietnam today would hinder rather than help

the campaign against the insurgency."

Robert S. McNamara,

Secretary of Defense

Washington, D.C.

February 17, 1964

Injuries such as the ones I photographed in my

operating room are really what prompted me to

write you the letter. The burden of what's on my

mind these days is really about patients such as

these. I admit I'm not terribly interested in

dominoes, or in Laos, or in who's threatening whom

in Cambodia or Thailand. My background is not in

power politics or in Southeast Asian culture; it's

in caring for patients and in trying to make sick

people well. I must admit I've had a terribly

difficult time trying to understand why these

young kids were being mashed in Vietnam when I

thought they should be back home growing a little,

or with their wives and children, or with parents

and friends.

Many of our patients' wounds covered a fairly wide

spectrum. Some men died in hospitals in Vietnam,

some died in the Philippines or in Japan, and some

died back in the States. Some survived to reach

veterans' hospitals, and some returned to civilian

life. There are some brain-injured men who will

one day resume the support of their families and

eventually return to ways of living pretty much

the same as before they went off to non-war. These

are the luckier ones who'll bear only a few scars.

Their less lucky comrades will have a paralyzed

limb, or two or three or four. Some will be quite

bright and alert again, but some will not be able

to speak, reason, protest or assent. It's for

these, a sort of silent majority, that I'm writing

you.

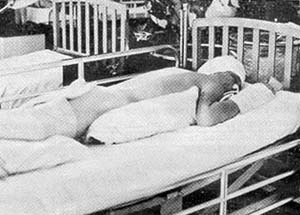

If you had visited our ward, you might have seen

young soldiers on their sides and facing down so

that they would not aspirate or breathe into their

lungs any excess secretions or vomit that would

make their situation more precarious. Tubes

carried moist air through small holes in their

windpipes, and this made it easier for the staff

to aspirate secretions and prevent pneumonia. With

a large number of unconscious patients, these

measures greatly reduced the incidence of

pulmonary complications. As you can appreciate,

these patients were unable to cough if they were

deeply comatose, and of course they were not aware

of the need to empty their bladders or evacuate

their bowels.

The Vice President's recent remarks that if we had

shown a little more backbone in the Republic of

Vietnam we would have won the war sooner reminded

me of one young man I had treated. He had a

complete loss of spinal cord substance in his

midback with resultant inability to feel or move

his legs. A small amount of bone protruded through

his surgical incision and this was obviously

infected, as was the surrounding tissue. We

discovered that the whole vertebral body, a fairly

vital part of this boy's backbone, was infected.

When I grasped the bone itself and pulled gently,

the entire segment released from its surroundings.

This is a fairly common maneuver in the autopsy

room on a cadaver, but I had never done this or

heard of its being done to a living person.

The Red Cross and other woman workers were awfully

helpful to our troops as they returned from the

combat zones. They would write home and let the

Stateside family know how the young soldier, soon

to be veteran, was getting along. Their aid was

invaluable with the sightless, paralyzed,

amputated, and mentally subdued, of course. In our

ward, these women often helped with patients

confined to CircOlectric beds. These beds were so

useful that I often thought the Veterans

Administration should see to it that each

quadriplegic patient who reached home received one

along with his discharge papers. These powered

beds were most useful at our hospital in Japan, as

the staff could adjust a patient's position not

only for comfort but also for nursing wounds other

than crippling spinal injuries. As you may

realize, one of the biggest problems in these

cases is that not only do the patients have no

movement of their limbs, but they also have no

sensation of their paralyzed parts, and these

areas may break down, become necrotic and thus

rather difficult to manage.

The wounds could be quite devastating to the

brain. I was impressed by the amount of brain one

could lose and still live, in a way. As I'm sure

you know, in most people, the brain is a fairly

important organ, and when mortar fragments, or

dirt, or splinters of bone scatter through the

head, it's pretty hard not to cause some fairly

extensive injury. One boy with a very damaged head

was so ill when he reached Japan that it was

apparent he was not going to survive to make the

trip home. His parents came over to spend his last

days with him. I might just mention the local

problem with the wound. You see, he had lost a

great deal of skull and brain covering along with

his scalp, and the wound and underlying brain were

infected and under very increased tension.

Well, in any event, Christmas Eve arrived, and the

children from one of the local schools were

serenading the wards of the hospital while this

boy's parents maintained their vigil. As the

youngsters came onto the ward, you could have

hoped for a little bit of a miracle, but instead,

the patient passed on at that moment. We all

celebrated Christmas in different ways that year.

"I have never been more encouraged in my

four years in Vietnam."

General William C. Westmoreland

Commander, United States Forces in South

Vietnam

Washington D.C.

November 15, 1967

I must sadly confess that from my vantage point,

we weren't winning very much. Clearly, it was a

long time ago that we were told we'd soon be done

with it. We were assured and reasssured that

victory was almost in sight. Now, I wouldn't

presume to contradict men who were my military

superiors, and I wouldn't for a moment question

the statements of either the elected

representatives of the South Vietnamese people, or

of our own field commanders and generals in the

Republic of Vietnam, but I would in all humility

submit that these boys and men who came under my

care were not cheered by the thought that we were

winning. These boys felt that they had lost; and,

of course, in a simplistic sense, I guess that

they had lost -- an arm, a few legs, some brain, a

little bone, a kidney, a lung or spleen, perhaps

some liver. I must sadly observe that despite our

cheery casualty statistics that we've killed

fifteen times as many North Vietnamese and

Vietcong as they've killed of us, the fact remains

that many of my patients felt that they had lost.

I guess it's difficult to avoid giving you the

impression that I'm sort of an anti-war kind of

person. I admit that I didn't feel too strongly

one way or the other before putting on my uniform.

It really took very little time to realize that

there were better ways of dying for one's country

than the ways we devised for our younger brothers

and neighbors. Not all my patients were draftees

or short-termers who were anxious to serve their

hitch and get out; we often had patients on the

ward who were career soldiers, and at times we

even had some officers.

"He was a farm boy who had worked in the

fields, and his family just didn't believe

sunstroke killed him.

"I checked into it, and the Pentagon reported

his face and body were reddened by the sun

while he waited three hours to be evacuated by

helicopter from combat.

"Finally they acknowledged he was waiting to

be evacuated because he had three bullet holes

in him. And they call that an incidental

death; Well, they changed it.

"The number of combat killed and wounded have

become so great ... they are trying to hide

it...a clumsy effort to deceive the public

about casualties in this most unpopular and

undeclared war."

Stephen M. Young

Senator from Ohio

Washington. D.C.

April 29, 1969

My own ward was fairly characteristic. Comatose

patients certainly can be seen wherever much

neurosurgery is being done, but we had a rather

large volume of them. The Army cared for its

paraplegic and quadriplegic patients with Stryker

frames and CircOlectric beds that provided

movements and changes of position the men could

not provide themselves. In our ward, we had quite

a bit of difficulty trying to decide who should

continue evacuation back to the States and who

should return to combat. I'm glad to hear that the

burden of making this decision has been eased, and

that all patients who reach Japan are now able to

continue home. I must confess this seems quite

reasonable; the other way seemed somewhat cruel --

almost like sending men back to combat because

they hadn't been hurt badly enough the first time.

I'd like just once more to reemphasize that I do

not intend this letter as criticism or expression

of disapproval. Why, you weren't even my

Commander-In-Chief during most of this time, and

the President who preceded you was being reassured

that the end was just around the corner, that the

enemy was on his last legs, that we had just to

buckle down a little longer and the coonskin would

be on our wall, etc.

I was happy to read not long ago that the Army

Chief of Staff has stated that the Vietnam War has

technologically been a great success. I assumed he

must have had in mind such developments as a MUST

unit. This is a Medical Unit Self-contained

Transportable and will certainly be useful in

situations where a small hospital must be rapidly

set up near a large disaster area. If I understand

the concept correctly, the idea is to send the

hospital to any area where large numbers of

casualties are being generated. I must apologize

at this point for a temporary diversion.

I had never before thought of sick or wounded

people as being generated. It's a concept I

learned during my indoctrination period at Fort

Sam Houston in Texas. You will agree, surely, that

it is a modern way of thinking about these

problems. It's clearly much nicer to sit in a

conference and hear about five hundred or five

thousand casualties being generated in a given

situation. It's a much nicer way to think of large

groups of people in this manner, somewhat like

electricity being generated at some power plant or

other. Well, in any event, I just never could get

it into my own head, or discipline myself to think

of my patients in this fashion -- being generated

here, stored there, transported, re-stored, etc.

This probably accounts for my hesitancy in being

more outspoken with that costs analyst from the

Pentagon. I just couldn't convince him that we

were dealing with patients, not packages.

I must confess that despite the nice commendation

the country has given me, and despite your

enthusiastic support during this conflict, I

didn't ever come to feel that being part of the

Army team was really my cup of tea. I just never

managed to get into the spirit of it.

This letter has far exceeded my original intention

of just jotting down a quick note; but if it's

provided you with any information or a viewpoint

somewhat different from what has reached you

through more standard and orthodox channels, then

it has certainly been worth my time. I do hope I

have not bored you, either, with my thoughts or

these photographs.

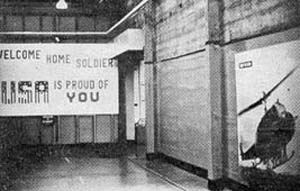

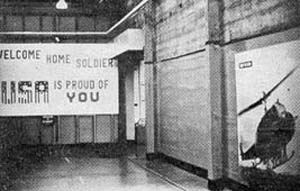

When I left active duty and was being discharged

through Oakland, I was gratified to see a

welcoming sign in the corridor. I regretted only

that my own patients who had been evacuated

through medical channels were unable to see this

concrete expression of their nation's gratitude.

"It simply does not matter very much for

the United States, in cold, unadorned

strategic terms, who rules the states of

Indochina. Nor does it matter all that

terribly much to the inhabitants. At the risk

of being accused of every sin from racism to

communism, I stress the irrelevance of

ideology to poor and backward populations."

J. William Fulbright

Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee

Washington. D.C.

I appreciated the opportunity of visiting Japan

and of broadening my medical experience during

that time. I regret that we lost so many men, not

only in Vietnam, but also in our overseas

hospitals. Some of the casualties were more

difficult to retrieve or repair than others.

Caring for the wounded is indeed a privilege; but

I was never able to convince myself that they had

been wounded for any good end. They were, after

wounding, and I'm certain before wounding also,

the finest men I've seen. But I cannot help but

point out my feeling that this war was unworthy of

them. They gave too much in that far-off place --

and we should not have sent them there.

I know that you deplore this conflict as much as

I, perhaps for different reasons. I did hope that

sharing these few pictures and thoughts with you

would in some way explain why I felt compelled to

submit my resignation as I did, rather than to

extend my time in the Army. There are, happily

enough, younger men now available to carry on the

neurosurgical tradition in and after combat. I do

hope that they are made of stronger stuff inside

than I, and that their tours of duty will not

remain in their minds quite so indelibly as has

mine.

Knowing how the military operates, I'm certain

that neither you nor your predecessors have had

the opportunity to see these scenes. We who were

fortunate enough to be brought into active service

as two-year doctors have, of course. When we

reported for duty, the threats that our orders

would be changed for Vietnam if we didn't extend

for a third year seemed somewhat hollow. None of

our group being indoctrinated at San Antonio was

cowed. Things evidently later changed, for we had

several men appear in Japan this past year after

having extended their tours of duty for that very

reason. I must admit that I was never terribly

impressed by the personnel procedures or

procurement policies of the Army. But if the

courts allow this practice to continue, then I

suspect the military may have found a way to get

one-and-one-half times as much wear out of this

former group of two-year doctors. I congratulate

your planners.

I really had hoped to send you this note while I

was still on active duty, but we were somewhat

busy most of the time, and my colleagues and

superiors cautioned me that it might be more

appropriate to allow a seemly interval to pass

before trying to record my recollections for you.

I'm afraid I'm leaving out a great deal that

seemed important to me at the time, but I'm

nevertheless able to recall a few glimpses of what

was occurring. I had been told that if I waited

long enough, perhaps the war would go away. I did

wait, but it didn't seem to go away at all...

It's hard to believe in war if you take the

preceding or following seriously.

Here are six Pictures without Words that appeared

in the LOOK article:

I know the aphorism that "a

picture is worth a thousand words," but I've never

felt that any picture or series of pictures could

equal the power of Dalton Trumbo's novel: Johnny

Got His Gun.

|